Over the years, I have had the pleasure of attending lots of memorable cultural events. Sometimes,

my memories of these events over time become transformed and condensed to just a feeling. Some

performances have left me emotionally elated, whilst others have left me drained. My one

persistent belief is that I always respect the creators of a piece of work even if I do not always

understand their original intent or indeed, feel that the work has worked for me. It doesn’t matter

because someone has made an effort to offer something of themselves to an audience.

Now, quite by accident, I stumbled on the work of Sarah-Louise Young. I suspect that I may have

seen her first as part of Roulston and Young with their catchy acerbic songs about relationships etc. I

then saw ‘Julie Madly Deeply’, a beautifully resonant exploration of the work of Dame Julie Andrews

and an equally touching engagement with her fans. I most recently saw her at the Soho Theatre

performing ‘An Evening Without Kate Bush’ from my little table in the B row with a friend and was

astounded that she brought out the hidden performer that lurks within, as ‘Wuthering Heights’ was

sung and I began the dance movements. Sarah-Louise Young is a very talented and versatile creator

touching on many mediums. She has very kindly consented to allowing me to interview her, so

without further ado…

In your current show, ‘An Evening Without Kate Bush’, you explore the works and life of Kate

Bush and her impersonators. You also acknowledge borrowing a wig from the oldest (and now

retired) Kate Bush impersonator.

I like to think the show explores Kate Bush and her fans, as opposed to her impersonators. We

do pay tribute to her original tribute act, ‘Jaquie’, who sings ‘Wow’, but the heart of the show is

about how each of us has our own relationship with her work and how we experience it or ‘pay

tribute to it in our own way’.

What attracted you to Kate Bush as the possible subject for a production?

I had always been a fan, but the original idea for the show came from my co-creator, Russell

Lucas. We had already had international success with ‘Julie Madly Deeply’ (our musical love�letter to Julie Andrews which has played West End and Off Broadway). The two shows are very

different, but that started us thinking about the relationship fans have with their icons,

especially someone like Kate, who hadn’t performed live for over 30 years, since her 1979 ‘Tour

Of Life’.

Interestingly the first work-in-progress sharing of the show was as a two-hander, with the

brilliant Matthew Jones (Mannish from Frisky & Mannish). We presented a 20 minute section at

The Albany in Deptford as part of their try-out night, Cabaret Playroom. We spent a few days

together in a rehearsal room but in the end decided to save our enthusiasm to collaborate on

something else as he wanted to focus on his Richard Carpenter show and it felt like the best

story-telling mode for this piece was for a solo performer. It was great fun to play together

though and some of the ideas we had begun to explore still made it into ‘An Evening Without

Kate Bush’.

After Russell and I had just started working on this version, Kate Bush suddenly announced her

‘Before The Dawn’ comeback dates at Hammersmith Apollo! As fans we were thrilled. But as

theatre-makers we were concerned. We thought people might think we were just cynically

trying to cash-in on her return by making our show. So we decided to shelve it for a few years.

Cut to 2018 and we went to see the brilliant US tribute band ‘Baby Bushka’ at the Moth Club.

Watching their audience leap about to ‘Hounds Of Love’ and enjoying old classics with guilt-free

abandon, we knew we had to make ‘An Evening Without Kate Bush’. Our idea was too fun to

ignore!

Also how did you go about learning the techniques and mannerisms of both Kate Bush and her

impersonators? Did you interview them and/or watch a lot of performance footage?

I never set out to impersonate her. She is unique. It’s amazing how many people tell me I sound

like her though. I perform all the songs in their original keys and I think part of it is that she chose

such specific phrasing and wrote such intricate melodies, hearing them instantly hot wires you

back to the original. I spent one day working with the amazing Tom Jackson Greaves, who is a

director and choreographer. He had watched a lot of her videos and noted down similarities in

her body vocabulary. We explored those in our session; again, never trying to ‘be’ her, more tap

into her spirit. Quite by accident, the nicknames we came up with for them (The Pulse, The

Champagne Whipcrack, for example) found their way into the show. That’s often how it happens

with devised work - you become a sponge for every impulse and they jostle around your head

during the making process until they either find a home or float off into the ether.

With the costumes too, we tried to evoke her, not copy her. We rub shoulders with themes (she

uses a lot of nature and bird imagery in her work, hence the feathery headdress). The cleaner’s

outfit for ‘This Woman’s Work’ is as much a nod to the cleaner’s story we mention at the start of

the show, as it is to her TV special appearance where she sang ‘Army Dreamers’ dressed as a

cleaner or archetypal vintage housewife. That’s one for the Super-fans.

We did of course watch a LOT of footage, interviews, videos, everything we could find, to get to

know her journey as an artist and also how the world around her changed. Her early interviews

are so uncomfortable. She is often being asked truly banal or overtly sexualised questions. She is

so polite and accommodating but it’s great to see her later on her career take the reins and shut

down lines of enquiry which show the interviewers have no idea what they are talking about. I

also read the brilliant biography by Graeme Thomson called ‘Under the Ivy’. It’s the best music

biography I have ever read and really lets you into her creative process.

When did you first become aware that you had a predilection towards performance? How did

you develop these skills through your education?

I come from a big family; I’m the youngest of five siblings and the only girl. Apparently that

explains a lot! I always loved to sing but was quite shy away from home until I went to secondary

school. I found doing silly voices helped me out of a tight spot at ballet once when the older kids

were picking on me for wearing second hand clothes. It’s a common story amongst comedy

performers that they find their voice under duress. We had the most brilliant music teacher at

school, Miss Porrer, and she really nurtured me. I have been fortunate to have a lot of

encouragement, from my family, my teachers and my friends. I met one of my closest friends,

Paulus, at 13 and he shared his love of cabaret and variety with me (I distinctly remember him

playing me a Fascinating Aida record in his bedroom, both of us surrounded in stuffed Garfields.

I had no idea that 22 years later I would be guesting with them in the West End!)

You suggest that a teacher found your performance during your teenage years as Kate Bush a

little risqué. Were other teachers more encouraging of your creativity?

I wouldn’t take everything you see in the show literally if you don’t want to spoil the magic :-)

How would you recommend a student in school or college with creative leanings should

develop their skills?

See stuff. Watch other performers. If you don’t have much money, like me growing up, talk to

your libraries, your school, your local theatre - they may have resources and outreach projects. If

you can get online there are SO many good shows available to watch. Also, just DO it. Don’t wait

for permission. The Edinburgh Fringe is an expensive place but there are ways to do it more

cheaply like the Free Fringe and it is an incredible learning experience. You have to try and fail

and as Beckett said, ‘fail better’. There are no short cuts. With every new show I make I start

again. Watch, devour, make, take risks, and study a bit. But don’t get stuck in an endless cycle of

taking courses, DO! Also get some sleep, look after your body and foster your friendships with

friends. You need a life too.

Who have your influences been as you have developed your own style and professional

career? Have they varied a great deal from your childhood interests?

There are performers and creatives I saw when I was young who inspired me to want to act:

Emma Thompson, Steven Berkoff (around the time of his incredible solo show, ‘One Man’), Linda

Marlowe (who I finally got to work with and is now a friend), Kathryn Hunter, Mark Rylance. Also

composers, Stephen Sondheim, Kurt Weill and artists as diverse from Edith Piaf to Joni Mitchell.

As we evolve so the need for different creative nourishment evolves. I am most inspired now by

my contemporaries, people making and evolving around me: Desmond O’Connor and Zoie

Kennedy (as individuals and as part of Twice Shy Theatre), Amy G, Lucy McCormick, Gateau

Chocolat, Peta Lily, Jordan Clarke, to name a few.

Also when did you first become interested in Julie Andrews? ‘Julie Madly Deeply’ still holds

fond memories for me. I saw it twice in the same run at the Trafalgar Studios, both alone and

with my mother and sister (who are big fans of Dame Julie Andrews). You successfully

conveyed the emotional attachment of fans to their idols. Did you ever meet Dame Julie

Andrews?

Thank you, I’m still very fond of that show and in fact we just did a two week run of it over

Christmas (at the Park Theatre in London). I have not met Dame Julie but some of her friends have seen

the show and loved it so that’s wonderful. I did invite her but she is a bit busy!

You work regularly with Michael Roulston and I have many happy memories of seeing the two

of you performing your songs in various venues. ‘Please Don’t Hand Me Your Baby’ from

‘Songs For Cynics’ has always been a favourite. When did you meet Michael Roulston and how

does collaborative working help you to develop your ideas? When Michael and your self are

composing, do you find that one or the other of you tends to focus more on the lyrics of a

song and the other person, the music?

We met on the Battersea Barge when it was owned by Peter Lewis who provided a haven for

artists and clowns to try things out, develop ideas and experiment. Paulus, Dusty Limits and I put

on a cabaret night called ‘Trinity’s’ and Michael played for us. We worked a lot in different

configurations and then in 2006 I asked him to write songs with me for an ill-fated show called

‘Confessions Of A Paralysed Porn Star’. The title was the best thing about it. By the end of the

run I was £8000 out of pocket but we had learned how to write songs and make a show. It took

me another three years to try again and by then I had learned from some of my mistakes and we

presented ‘Cabaret Whore’ in 2009 which catapulted me into the world of cabaret one-nighters,

The Adelaide Cabaret Festival and being commissioned to make ‘Julie Madly Deeply’. At the start

I was very much the lyricist and Michael was the music but now we have a more fluid working

relationship. We still have our feet primarily in those camps but will work together on a lyric first

and then on the music and it’s just as likely that Michael will solve a lyric problem as I might

have an idea for a melody. It’s a true collaboration.

Also the idea of creating bespoke songs for individuals is a unique endeavour. How did the

idea come about?

Like many creatives the pandemic wiped out all of our work for a year. We had already written

songs with and for other people (including Marcel Lucont, Lili La Scala, Ophelia Bitz, Clementine

Living Fashion Doll and TO&ST winner, Lynn Ruth Miller). We put the idea out on social media

and the response was great. We’ve written songs and created personalised photo videos (with

the lyrics so you can sing along) for birthdays, weddings, retirements, Christmas, Mother’s Day,

Valentine’s Day and even a song for a cat. We are still doing them now.

I recently saw the production of ‘Jarman’ that you directed. How did you become involved

with the playwright and actor, Mark Farrelly and can you explain to me some of the freedoms

and restrictions that you experience as a director as opposed to those situations where you

are solely responsible for your own work?

I met Mark in the queue to see the brilliant Rob Crouch in his solo show about Oliver Reed, ‘Wild

Thing’. He was about to make his Quentin Crisp show and I was about to start work on ‘Julie

Madly Deeply’ so we were seeing as many solo shows as we could for inspiration. We became

instant friends and big fans of each other’s work. When he asked me to read his script for 'Jarman' I didn’t know a lot about him other than the title of some of his films and as an activist. I

fell in love with the script and the man and then watched his films and was delighted to be asked

to collaborate on the piece. I don’t really think of directing as having restrictions - my job is to

help the artists create the show they want to make. In the case of ‘Jarman’ the script already

existed so my job was to bring the physicality and staging to it - a visual realisation. We made a

few small adjustments to what was on the page but it’s mostly exactly as Mark wrote it. I

absolutely adored working with him and found him endlessly open and available for play and

exploration. I’m very proud of the show. I’m also working with Russell Lucas on a new show

called ‘The Bobby Kennedy Experience’ where he is performing and I am the outside eyes. It’s a

different process from the one I had with Mark - again, there is no template: sometimes Russell

will work on things on his own and invite me round to give feedback. Sometimes we are coming

up with ideas together. With ‘Looking For Me Friend: The Music Of Victoria Wood’, Paulus,

Michael Roulston and I spent a few days listening to songs, playing with post-it notes and

collecting stories and quotes. Then Paulus went away and wrote the script. So I had a bit more of

a hand in its creation but my job as director is still to facilitate Paulus to make the show he wants

to perform. The kind of work I make for myself often involves improvisation and flexing with the

audience in the room - so that is in and of itself a different kind of freedom. As a director, once

the show is out there, my influence is over - apart from sitting in the dark and feeling proud.

‘Je Regrette!’ was a very funny and in some respects, hard hitting account of an Edith Piaf style

figure with her difficult upbringing. What paths lead you to create a figure based on the

troubled singers of so-called chansons or torch songs?

La Poule was originally one of 7 characters in the ‘Cabaret Whore’ series of shows. She’s the only

character who made it into all four incarnations. She’s my dark clown. She comes from the

desperate human need to be loved, the narcissistic neediness in a lot of us. She’s inspired by real

people and imagined people. The original premise of ‘Cabaret Whore’ was to look at the ego it

takes to stand on a stage and tell a bunch of strangers your life story. Why should we care? It’s

the question I start all making processes with. What are we asking the audience to connect

with? Who or what is it in service to? Again, it’s less about trying to imitate or reference a

specific singer. La Poule just happens to be a singer. Mostly she’s a human being who has found

life hard and unfair. I think a lot of people can identify. I use extreme characterisation to amplify

normal behaviour so that audiences can recognise aspects of themselves but feel reassured they

are not THAT bad!

During your production, ‘An Evening Without Kate Bush’, you delve into a box of costumes and

props? Was this something you used to do as a child?

My childhood friend Charlie had a huge costume box I was very envious of and we used to get

given huge bags of second hand clothes from well-meaning people because we didn’t have

much money. I was always trying to create fetching outfits. At 14 I started dying my hair and

playing with that, shaving it off, making it blue. Now I dress up for a living. I’m quite dull in my

civilian life. I don’t wear make-up and I’m mostly in black. I like full transformations from simple

changes.

Also following your work in ‘The Showstoppers’ improvisation group, do you think that

improvisational practices are not only of use within creative endeavours, but also to explore

personal issues or dilemmas?

Absolutely and to answer that question I refer you to Pippa Evans’ book ‘Improv Your Life’.

Please can you explain your work with ‘The Authentic Artist’?

The AA is a wonderful collective founded by Kath Burlinson who runs courses and workshops for

people who want to explore their artistic process. She takes an embodied approach and I have

found this invaluable in my work. Writers, singers, musicians, visual and digital artists, set-designers, she works with all manner of creatives: they do not all necessarily practice their art

for a living. The group is not an official organisation, rather a gathering of like-hearted people

who have all experienced a similar process and like to stay in touch and share work and thoughts

from time to time. It isn’t a cult or a membership thing. It’s community.

Do you feel that there is a story within us all? If so, how would you encourage someone to

develop it?

I think we are all creative and we are all story making creatures - we tell stories to ourselves

when we sleep and we recount the day’s event with a beginning, a middle and an end. A lot of

people have their creativity squashed over time and I advocate everyone being encouraged to

invite in their creativity. Whether that’s how you arrange the furniture in your room, make a

salad or write your Facebook post.

During ‘An Evening Without Kate Bush’, you were able to encourage through your charisma

and empathy to get various members of the audience up on stage to both sing and dance.

How can you determine who will and won’t be willing to perform with you on stage?

I hope after 20 years of performing I am a good judge of who will want to play. I can definitely

tell who doesn’t want to be asked. I build into the show opportunities for me to investigate who

might be a possible contender for later in the show. Most people self-select - you can read their

body language and their faces (an interesting challenge through a mask!) I never invite a single

person up unless they have someone waiting for them by their seat to make them feel

supported when they return. I never humiliate people. My job is to elevate and celebrate the

audience. So far, no-one has every refused!

Where do you get your ideas from and how do you distinguish the form that they should take

(e.g. a song or performance piece)?

I’m constantly trying to make sense of life through my work. Everything is a potential inspiration

and the form it takes is dictated by what mode (song, poem, play, tweet) will serve it best. It has

to connect with an audience, so if it’s not going to resonate with someone else, I keep it to

myself.

Has your creativity ever led you astray resulting in you creating something unlike your original

idea?

I don’t think I have ever made a show with an exact version of it in my head at the start. If the

story is solid then there is a direction of travel but it’s part of the creative process to wander off

path from time to time. I am making a show now for Summerhall this August called ‘The Silent

Treatment’. I was just about to share an early draft when Covid hit. During the past two years it

has morphed into a different show, hopefully a better show than the one I might have presented

in 2020. The world changed, I changed, so it changed too.

I haven’t read it yet but the ‘RSV People Book’ by Paul Chronnell and your good self sounds

wonderful (the book is on its way to me now). The idea of contacting all of the requests for

pen pals in one issue of ‘Smash Hits’ magazine in 1985 touches on a theme that seems to run

through lots of your projects. Nostalgia seems to provide a rich vein for your creativity. What

do you most miss about the past?

Flexibility and time. I don’t really miss the past but I long for more TIME - time to do nothing -

life is full and I love it but I sometimes long for a few days with absolutely nothing to do but

shoot the breeze… if I had it I’d probably spend it coming up with an idea for a show anyway! I

also have to stretch and look after my body much more now than I used to. But honestly, each

year I am learning - I wouldn’t want to go backwards.

Your work ensures that certain acts and movements are not forgotten, how would you like to

be remembered?

As someone who cared and told good stories. Loyal and loving. Work in progress up to the final

breath.

What are your future plans? How is your musical ‘Maxa, The Most Assassinated Woman In The

World’ with Michael Roulston coming along?

There is a lot of promotion to do for the book. ‘Jarman’ and ‘Looking For Me Friend’ are off on

tour so I will check in with those. I have one more week working with Russell on the 'Bobby

Kennedy Show' before we open at the Town And Gown in Cambridge in April. After our Soho run

I am on tour with AEWKB (‘An Evening Without Kate Bush’), I’m also in rehearsals for 'The Silent

Treatment' and coaching several other artists on their solo shows and planning a wedding. Maxa

is ready to go so now we need investment or a producer to take it on. It’s all go!

Sarah-Louise Young, many thanks for allowing me to interview you and I look forward to

seeing your next production.

Barry Watt – 9th February 2022.

Afterword

Please see the below links for further information about Sarah-Louise Young and her

endeavours/collaborations:

Sarah-Louise Young’s website: www.sarah-louise-young.com

Bespoke Songs: www.roulstonandyoung.co.uk

An Evening Without Kate Bush: www.withoutkatebush.com

The RSVPeople: www.thersvpeople.co.uk

Maxa Musical: www.maxamostassassinated.com

The Authentic Artist: www.authenticartist.co.uk

Also all of the projects/artists/magazines and books etc. are copyright to their respective owners.

BW.

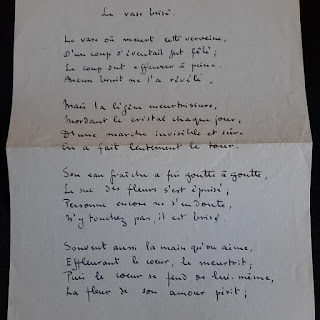

Photos (Kindly provided by Sarah-Louise Young. The photographers are listed under the photos. As above, the images are copyright, so please do not use without seeking permission or La Poule may come to visit with her knife! ;-) )

Sarah Louise Young (Photo by Jamie Zubairi)

An Evening Without Kate Bush Main Shot

(Photo by Steve Ullathorne)

Roulston & Young (Photo by Claudio Raschella)

Julie Madly Deeply (Photo by Steve Ullathorne)

La Poule Portrait (Photo by Steve Ullathorne)

|

La Poule With Knife

(Photo by Steve Ullathorne) |